Appendix II - Relevant Atmospheric Processes #

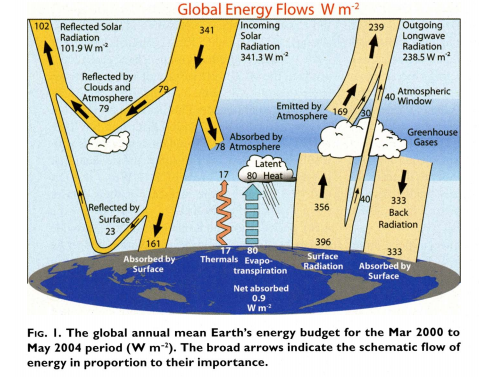

Heat flux through the atmosphere as summarized in Kiehl, Trenberth (2009) \({[^6]}\)

Surface heat is transported vertically by the following means: reflection, thermals, evapotranspiration and net difference between surface radiation and back radiation.

The direct surface heat transfer processes relevant to this proposal are thermals and evapotranspiration. Back radiation can be affected over a longer timeframe by the improvements to the efficiency of photosynthetic processes as a result of the deployment of the technology proposed herein.

A) Thermals #

A gas atmosphere in a gravitational field that is in thermal equilibrium exhibits a temperature gradient that is determine by the gravitational field. This is known as the atmospheric lapse rate and is as a result of the direct relationship between pressure and temperature in a gas. Air pressure is dependent on altitude due to the compressibility of gas and the action of gravity. The lapse rate for dry air is 9.8°C per 1km gain in altitude, from:

\[\Gamma_d = - \frac {dT} {dz} = \frac g {c_p}= {9.8 \degree C} / {km}\]Where \({c_p}\) is the specific heat of air at constant pressure and g is the standard acceleration due to gravity. When air is fully saturated (100%RH) and moisture is condensing into liquid droplets, the heat of vaporization is released into the air which has the effect of reducing the lapse rate below that for dry air. The lapse rate for moist air, as used by the American Meteorological Society, is given by:

\[\Gamma_w = g \frac {1 + \frac {H_v r} {H_{sd} T} } {c_{pd} + \frac {H_v^2 r} {R_{sw} T^2}}\]With variables as in:

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| \(\Gamma_w\) | Wet adiabetic lapse rate (K/m) |

| \(g\) | Standard gravity |

| \(H_v\) | Heat of vaporization of water [2501000 J/kg] |

| \(r\) | Mixing ratio of the mass of water vapour to the mass of dry air |

| \(R_{sd}\) | Specific gas constant of dry air [287 J/(kg K)] |

| \(T\) | Temperature of the saturated air (K) |

| \(c_{pd}\) | Specific heat of dry air at constant pressure [1003.5 J/(kg K)] |

| \(R_{sw}\) | Specific gas constant of water vapour [461.5 J/(kg K)] |

Thermals are driven by convective uplift, where surface heat flux (primarily solar gain) raises surface air temperatures above the equilibrium state as established by the lapse rate. This surface air is now more buoyant than the air in the column above it and consequently the surface pocket of warmed air rises through the atmospheric column – this is the process of convective uplift. It should be noted that the temperature of this pocket of air is governed by the dry and wet lapse rates as it rises vertically.The air pocket will remain warmer, and thus more buoyant, than the surrounding air until mixing and conduction processes have resulted in its buoyancy equilibrating to the surrounding air. In this way surface heat is transported vertically through the air column by thermals.

B) Evapotranspiration #

Incident solar radiation not only directly warms the surface, it also acts to drive direct evaporation from surface water and the transpiration of moisture by plants engaged in photosynthesis. The evaporation of water results in direct surface cooling (the water absorbs the latent heat of vaporization from its surroundings), whilst also making the air into which the water vapor has moved more buoyant. Water vapor is more buoyant than dry air due to its lower molar mass, resulting in moist air being more buoyant than dry air. Consequently, evapotranspiration processes result in buoyancy driven convective uplift of moist air pockets. These air pockets are subject to lapse rate cooling processes as described above, which eventually results in the temperature of the rising air pocket falling below the dew point of the water it holds. This leads to precipitation, which releases the heat of vaporization during the condensation process – this means that the heat of vaporization absorbed from the surface has been transported vertically and released at altitude.

C) The Atmosphere as a Heat Engine #

“The atmosphere acts as a heat engine that converts internal energy into kinetic energy through a combination of warm, moist air expansion and cold, dry air compression \({[^7]}\) . This is the means by which the wind that drives wind turbines is generated and the water that fills hydro-electric dams is moved from sea level to high altitude reservoirs.

These processes are harnessed in a purpose designed structure, with the addition of convective heat transfer in waterthat relocates surface heat to a desired altitude by means of a hydraulic circuit that utilizing the natural atmospheric temperature profile (see Fig. 2). The hydronic heat is transferred back to the air at the desired altitude within the structure, resulting in this warmed air rising due to convection. The structure is designed such that the buoyant volume of this warmed air is able to draw up heavy/cooled air from the structure below it. The work done by the upper warmed air lifting up the lower cooled air results in further cooling of the lower air parcel.

Thus, convective heat transfer in water, which is able to relocate surface atmospheric heat which is not being transferred convectively in the air, coupled with convective atmospheric uplift in a flue-like enclosure provides the basic elements to constitute a Convective Heat Engine that performs atmospheric cooling which can be utilized to provide the useful services outlined in this proposal.

[6] Kiehl, Trenberth 2009 #

https://journals.ametsoc.org/bams/article/90/3/311/59479/Earth-s-Global-Energy-Budget