Appendix I – Urbanization Implications #

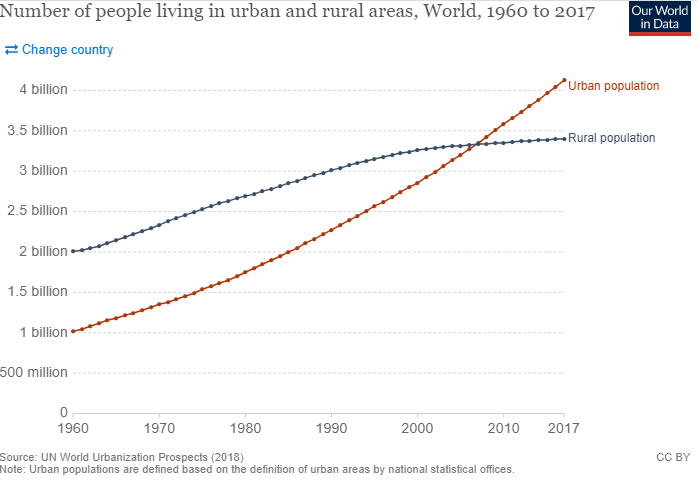

Global population is trending towards increasing urbanization, with some 55% of the global population living in urbanized locales as of 2018 \({[^3]}\) , with the recent urbanization rate being around 800 million people per decade.

This trend, coupled with a summer Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) effect of 1.9°C and winter SUHI of 0.87°C (USA results \({[^4]}\) ) demonstrates that the majority of humans are living in environments that are warmer than the natural surroundings. So, increasing temperatures experienced in urban environs are well above the warming which has been measured by means of the global averaging method used to measure Global Warming / Climate Change. It thus logically follows that urban environs are likely to be the “bleeding edge” with regard to the impacts of climate change, being measurably hotter than the surrounding natural environment in which they are located.

Urban environments are also, by definition, the environments with a higher human population density than the surrounding rural environs. This creates a unique motivation to solve the problem. The problem has been framed as Anthropogenic Climate Change – the human factors driving the change in climate. Thus, the place where the problem is greatest in terms of direct temperature measurement is also the place where the most direct human activity, and thus CO2emissions, occurs. It would seem that a solution that directly addresses the behavior of the problem at source would be advantageous. The problems of urbanization have long been recognized by the architectural profession. The concept of the vertical city is an attempt to address this.

The Vertical City project \({[^5]}\) represents the views of some of the pre-eminent architects around the globe, with experience in delivering some of the tallest structures ever built. The guiding philosophy is aimed at sustainability, with a view to having the structure contributing to the energy supply of in-building requirements. The CHE proposal builds on that vision by proposing a structure that does not just minimize environmental harm, but actually adds to environmental health by reversing anthropogenic effects on the environment as well as catering for its own needs.

The depiction of the CHE in Fig. 4 represents one example of the technology required for the proposal to function as described. The vertical CUTs are lined with fabric to allow for the movement of a compressible gas without structurally stressing a rigid envelope which would be subject to large forces with relatively small pressure fluctuations. This design approach leaves the perimeter of the structure exposed to wind loads, which the proposed fabric lining of the CUTs will be unable to withstand. The problem of protecting the CUTs with a robust perimeter can be solved by building a perimeter comprised of accommodation units, not unlike a conventional high-rise building. This solution turns the CHE into vertical city as envisaged above, with the added benefit of producing surplus power and water.

So, how does the CHE change urban behavior?

- People are moved from surface dwelling into tall towers, greatly reducing the surface area of roofing, roads and paving that is associated with SUHI.

- The reduction in roads is directly associated with a reduction in driving – less CO2 emissions associated with personal transport. Personal transport will mostly be associated with transport BETWEEN urban nodes, with local transport being more likely to be walking and cycling due to the radical change where people live.

- Land previously devoted to surface dwelling can be rehabilitated to “photo-synthetically” productive land – i.e. the land will be available to be covered in plants. This temperature of this land will likely be closer to the natural environment than traditional urban land.

- The CHE produces water, which will serve to keep the local environment well-watered. This will likely make the local environment more efficient at sequestering CO2 since water stress will be greatly reduced. Risk of fire as a result of dry conditions in the environment surrounding the “tower”, due to the continuous availability of water, will consequently likely be greatly reduced.

- The CHE produces its own continuously renewable energy, not requiring mining of the surrounding environment for fossil fuel resources. By turning previously paved areas into vegetated land, it is very likely that converting traditional urban locales into that alluded to here will be carbon negative in the medium term.

- The CHE directly cools the surface by increasing the rate at which surface heat is transported vertically through the lower atmosphere. In the Case Study included herein, each CHE continuously rejects 29.8GW of heat from the surface. So, whereas traditional urbanized environs absorb extra surface heat, the CHE reverses the heat flow of surface heat.

- More food can be produced locally on land reclaimed from the rehabilitated urban landscape. This reduces “food miles”, with associated climate benefits.

[3] UN World Urbanization Prospects 2018 #

https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Highlights.pdf

[4] Chakraborty et al., 2020 #

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924271620302082